Update (1/3/18) I’ve been overwhelmed with requests for the shorter guide, and the email address below no longer works. So I’ve uploaded a copy of the guide for anyone to download and share here: How to read and understand a scientific article. Please feel free to use it however you wish (although I’d appreciate being credited as the author). I apologize to everyone who emailed me and didn’t get a response! If you would like to let me know who you are and what you’re using it for in the comments below, I’d love to hear!

Update (8/30/14): I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu.

Last week’s post (The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google) sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article. It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article. Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: google “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed. [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals.

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this, then go back to my last post and read one of the papers that I linked to (like this one) and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

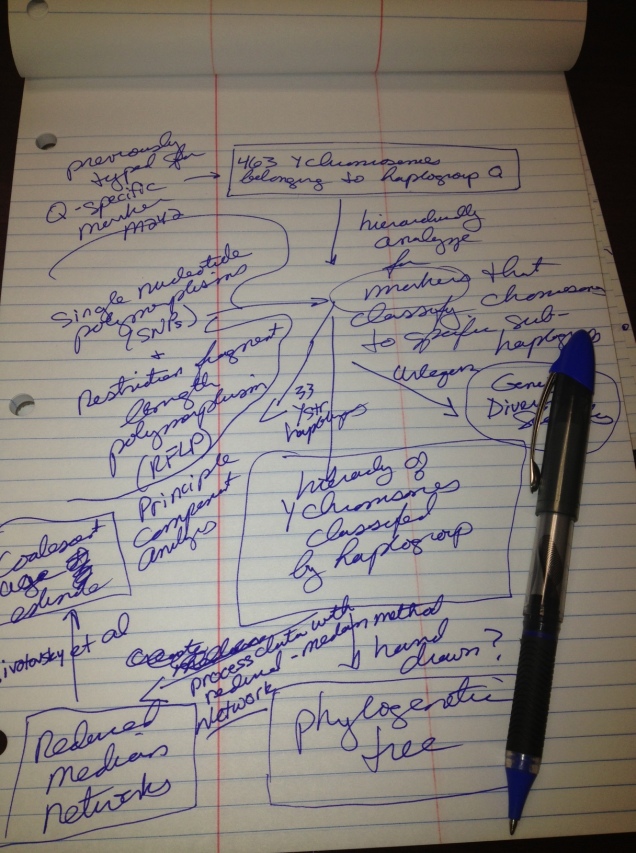

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today (Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q”). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean, just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here, here, and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

THINGS TO PAY ATTENTION TO IN THE RESULTS SECTION:

-Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here.

-If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

-The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

Now brace for more conflict– next week we’re going to use this method to go through a paper on a controversial subject! Which one would you like to do? Shall we critique one of the papers I posted last week?

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example, you can find one here

———————————————————————————————————

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

Do you have anything to add to this guide? A completely different approach that you think is better? Additional questions? Links to other resources? Please share in the comments!

Been reading papers for a few months and I feel I’ve gotten better but this will help a lot! Thank you for this guide!

ok i only knew a few of those,so that’s good..thank you!!

Ok i only knew a few of those,that’s good.Thank you!

Lovely, completely logical explanation that I’ll share with my students.

good job

Hello! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a group of volunteers and starting a new

initiative in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us useful information to work on.

You have done a wonderful job!

Excellent guidelines. I will share this with my class of evolutionary biology undergraduates.

sounds good.

This was vital information, I wish I would have read this before doing my senior seminar presentation!

Thank you for your post! After reading ten Facebook posts about vaccinations I got fed up with the comments and decided I had to post about reading critically. I was so thrilled that in the first sentence your too were writing after reading anti-vaccine writing! Thanks for writing a “Research for Dummies” version.

Suured tänud! – eestikeelse edastuse eest.

Minul on teistlaadi probleem:

Olen alati usaldanud “loogikat matemaatikas” – ja kui see lonkama hakkab – peab olema midagi väga mäda.

Õppisin (kuni 1959) keskkoolis:

– Zeno(ni) apooria (mitte paradoksi!?) vastu lõi Galilei Liikumisteisenduse, sihil x, kujul (x´= x – vt);

– juba 1905-ndast aastast alates oli väljatöötatud (Lorentz ja Poincare´) nn. “Aeglaste elektronide kinemaatyika-teooria”, mille SISUKS ja põhiprintsiibiks sai: “Elektron liigub täpselt niiviisi, et ei oleks täheldatavad tema liikumisest tekkida võivad efektid”;

– 1907-ndast aastast aga on millegipärast SUNNITUD needsamad teadlased möönma, et /… kuna MEIE ei oska mõõta relatiivse ruumi (kiirusel v liikuva inertsiaalsüsteemi) RISTMÕÕTMEID, kiiruse v sihist – seetõttu tuleb LEPPIDA “Einsteini hüpoteetiliste postulaatidega…”?!

– alates 60-ndaist aastaist (“Terrell pööre” ja nt. fakt et Doppleri ristefekt on teist järku suurus…) – me ei tohiks enam leppida “postuleeritud teooriatega”!?

NÄIDE alternatiivist: {x´= x – vt; y´= ky},

milles k = 1/L ja l – on nn. Lorentz-tegur.

//k – ongi see suurus, mis muutub ainumääravaks, “kiiruste v ja c võrreldavaiks muutumisel” (näiteks prof. Paul Kard andis kriteeriumi “piirnurgast a”: f(ct) = k(ct);

ehk siis: ( 1 – (v/c)cosa)) = (+,-)(1 – (v/c)^2)^(-1/2); ehk intuitiivselt:

“alates nurgast a, millal liikumisteisendus (ruumis) f = k; – nii et “teisenenud raadiusvektor r´= y´://

PS. Füüsikud EI TOHI seda lugeda, teised “ei oska”!?

Excellent guidelines. I will share this with my friends.

Good article. One thing missing though: When reading a scientific article make note of what is NOT stated. Anything that is not stated explicitly wasn’t done. Don’t interpret.

If you find yourself jumping to an ‘obvious’ conclusion from what you think you read – and it isn’t a conclusion that the authors drew – then your conclusion is almost certainly wrong. Remember that the authors are likle more intelligent than you and have worked on this for years. If they can’t find (statistical) evidence for an ‘obvious/trivial’ conclusion then it almost certainly isn’t in the data.

Perfect article, just what I was looking for. As a lay person of reasonable intellect, it is so hard to wade through scientific papers on unfamiliar subject matter. I’m presently in the midst of a difficult conversation about whether to immunise or not and my trust in the scientific community has been weakened by some of the anti-vaccinators and the references they are making.

Hopefully, by reading your article and ploughing through a few of the relevant scientific papers, I will be able to make a more cogent argument in the defense of vaccination. Or at least reconcile my own mind to the fact that I have done the best thing for my children.

Thank you! I wish you luck with your reading…please let me know how it goes.

Another way to determine if a journal (or ANY serial publication) is peer reviewed is by using a resource called Ulrich’s Web. Virtually all university and college libraries have a subscription to the service, as well as many public libraries – ask a librarian if you have access (or alumni access from a university). You can also use it to search for journals in the field that you are interested in, from medicine to theoretical physics to ancient pottery.

http://ulrichsweb.serialssolutions.com/login

Reblogged this on Dhananjay's Blog and commented:

Yep, that should help me understand research papers.

Great information. Very well written. Thanks for sharing.

I think this is a great article and thank you for posting it on-line! Although your target audience are people non-scientists, I think that there is a lot of good advice for scientists to follow (undergraduates and well-heeled scientists too boot)! I very much agree that reading the abstract is not enough. You really do have to read the intro, methods, results and discussion/conclusions to get any real idea of what the papers research is about for you then to be able to make your own conclusions. I have also always found it invaluable to read the references sections as it helps to get more background on the subject (if not covered sufficiently already) and get more information on how experiments/studies were conducted. Finally, as already mentioned in the article, you can always contact the authors if needs be for further clarification/information.

I will add something to this. As one who reads papers for a living you must also realize that scientists are human. You must ALWAYS read the papers with skepticism and to try to tease out was in which the authors gloss over crucial details.

For example, when examining statistical studies or models, you must learn about the science behind those methods. Doing this will help you to understand that when a scientist says “our model predicted X” you will understand that what the scientists is ACTUALLY saying is: “our model’s variables, weighted in the manner that WE think is appropriate, predicted X”.

This usually isn’t an issue, but it can be, especially in politically charged or highly competitive fields with a LOT of research grant money on the line.

That’s the one thing missing from this article…and given the increasing occurrences of scientific fraud (stem cell results for example) it is egregious that this wasn’t included in this otherwise good article.

Papers in “politically charged or highly competitive fields” indeed must be read with skepticism.

For example, I find it quite interesting (and mentally challenging) to follow both sides of the gun rights/gun control debate. There’s a great deal of lying on both sides, well-supported in many cases by cherry-picked “statistics.” The old saying applies to both sides: “Often wrong, but never uncertain.”

Thank you for writing this. I will have to check out the links for the information on statistics (even though I kind of dread it!). I am in the midst of researching vaccines and trying to make an informed decision for my family. It has been a long time since I have had to read research papers! I have read a few safety studies and have found that they were using an older form of the vaccine that they are currently studying for the control group. Can you point me to some safety studies that have better control groups than that? What do you look for in a safety study to see that it is a quality study? Thank you!

I will immediately take hold of your rss feed as I can not find your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service.

Do you’ve any? Please let me understand so that I may just subscribe.

Thanks.

Magnificent article… just a small detail… your “write down every word you don’t understand and look it up after” should not only apply only when reading papers. any word we don’t understand should be looked after. thats how we getter better at our own language and others…

Very nice article. Couple of thoughts, though:

I think it might be a bit of a hard read for lay persons. I mean, *I* can see what you’re getting at because I’ve previously educated myself on how to read scientific papers. For the lay person it may not be so obvious why one would have to go through all those steps.

Another thing that seems to trouble the lay person is the very language used in science. Maybe it’s for another article on the subject, but a lot of lay people are VERY confused by the “weak” language used by scientists. Everything is so couched in doubts and ifs-and-buts that especially the doubters can always find fault or claim. Remember they’re used to reading journalistic articles that seem very sure of themselves in their conclusions. A lot of science is much more sure of itself than it lets on.

Yet another useful thing to know is that there are important principles of science, or else nothing makes sense. For instance a lot of a papers operate with a 5 percent error margin (0.05). It can be useful to know that even in a hundred papers that really, truly did everything right there’s still five studies that might accidentally report completely opposite results to the massive, scientific consensus. This keys into yet another important concept in science: that there’s rarely One Proof nor “one study to rule them all”. Understanding that it’s the *convergence* of many studies, and even several scientific fields, that constitute the “ultimate proof”, helps put a single paper in perspective.

Anyway, especially for the lay person with a bit more time on his or her hands the book “Bad Science” by Ben Goldacre is an accessible source that helps the lay person navigate safer through the many pitfalls of science-meets-journalism-and-vested-interest 😉

This is great! Thank you for sharing this valuable information.