Update (1/3/18) I’ve been overwhelmed with requests for the shorter guide, and the email address below no longer works. So I’ve uploaded a copy of the guide for anyone to download and share here: How to read and understand a scientific article. Please feel free to use it however you wish (although I’d appreciate being credited as the author). I apologize to everyone who emailed me and didn’t get a response! If you would like to let me know who you are and what you’re using it for in the comments below, I’d love to hear!

Update (8/30/14): I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu.

Last week’s post (The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google) sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article. It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article. Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: google “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed. [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals.

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this, then go back to my last post and read one of the papers that I linked to (like this one) and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

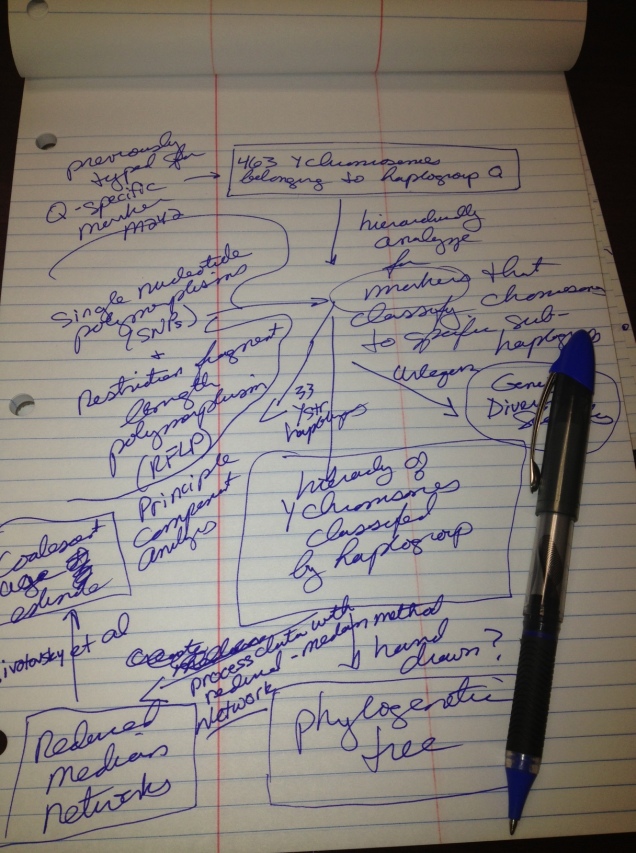

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today (Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q”). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean, just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here, here, and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

THINGS TO PAY ATTENTION TO IN THE RESULTS SECTION:

-Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here.

-If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

-The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

Now brace for more conflict– next week we’re going to use this method to go through a paper on a controversial subject! Which one would you like to do? Shall we critique one of the papers I posted last week?

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example, you can find one here

———————————————————————————————————

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

Do you have anything to add to this guide? A completely different approach that you think is better? Additional questions? Links to other resources? Please share in the comments!

Great article – I also like previewing – reading the sub headers and fig captions so my brain has a map to follow, I think you can do it without falling into the authors POV..

You left out one important step in the Initial review: Go to the “Acknowledgements” section and look at who is mentioned and at their professional relationships, in particular look at who provided the funding for the study. In a very general manner of speak, if the paper was funded by a grant from General Mills and the paper suggests eating wheat once a day at breakfast increases daily cognition, there’s a good possibility the conclusion was written before the study was ever done and the experiment was designed to give that conclusion. That’s not science, though, it’s politics! Truth, Lies and Statistics should be on every person’s shelf!

“Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.” – Do you know how much those papares cost? Quite many have no other choise but read only the abstract.

ttyl #yolo

Great article in most respects.

The only thing I would criticise is an omission.

You are describing a process that applies to certain types of research projects. It does not apply to a large portion of the research performed in the area of teaching skills to people with autism. This article mainly relates to studies that use the hypo-deductive method as opposed to research that uses a inductive data driven analysis of functional relations. Unfortunately, many researchers come from universities where there is not a strong understanding of the inductive method and as a consequence incorrectly criticise research based on the alternative model.

If you look at something like the National Standards Project, it found that a large portion of effective interventions are behavioural (90%+). This research often depends on single subject design. There are many advantages to single subject design (and of meta and mega analyses) but if the rule provided around the number of participants might lead people to believe that they should dismiss single subject research due to small n designs.

For more information, this article might be useful:

http://www.asha.org/Publications/leader/2011/110607/Deciphering-Single-Subject-Research-Design-and-Autism-Spectrum-Disorders.htm

Pay close attention to the methods and things that are left out. For example when doctors diagnostic procedures change. Did you know they test woman for HPV before testing them for cancer? No wonder women with HPV are more likely to be diagnosed, they send women without HPV home without further tests.

“Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.”

Excellent suggestions. I also support your optional advice to peruse the references cited in a paper. I agree that this is an important requirement for any scientist. I have been repeatedly shocked at how many graduate and post-doc students have ignored this during journal club reviews.

Merveilleux article, persistez de cette manière

I’m barely monolingual, but I’ll attempt to translate.

“Marvelous article, please continue the manure.”

That’s the meaning, and unless you’ve been insulted by Frenchman, you have no valid opinion on the topic. And don’t try to confuse me with any of that science stuff or professional translators, They are all controlled by Big Lingua anyway. They control the funding for translators, so they all have to do whatever Big Lingua tells them or they will be fired.

How do I know?

Because Glenn Beck proved it. He used a whiteboard and everything.

Does the hepatitis B vaccine cause multiple sclerosis.

identical twin with MS, your chances are 1 in 4,

although both twins do not always have MS. An orchestra consists of many musicians with different instruments.

Swedish massager has chinese culture shown results. They have found that

their acupuncture degrees, but there is a very safe and relatively non-invasive for so long as the needles

are inserted into the skin.

This is awesome, Jenny. Remember when we taught that little old class together called Information Literacy in Biology? Good times. We could have used this piece back then. Hope you are well! Send me a note sometime.

This study was funded by pharmaceutical giants. How is that not bias?

“On-time Vaccine Receipt in the First Year Does Not Adversely Affect Neuropsychological Outcomes” was funded by pharmaceutical giants. How is that not bias?

Please post the direct quotes from actual paper to support your claim. Because the financial disclosure just says:

It does not say anything about the funding being done for this particular paper.

Still, even if it was funded through pharma money, what does the data say? What about the other papers that come to the same conclusion (listed to the right of the paper)? What about this entire list: Vaccine Safety: Examine the Evidence.

Jennifer- Nice post. Vaccines aren’t a problem topic for me (I already believe you :-), but have unfortunately had to learn a lot about Celiac disease, a topic area primary care doctors may not be solidly on top of.

I’d like to suggest a useful search adjustment, from a note I send (Tone of Voice Change ahead) to weary Celiac friends:

—

site:*.edu filetype:PDF “abstract” “YOUR SEARCH TERMS GO HERE, WITHIN ONE OR MORE SETS OF QUOTES”

This search lowers the nonsense level by using search operators to narrow your results. The “site” operator above restricts results to educational institutions. The “filetype” operator restricts results to PDF files only (published research papers can more or less be expected to exist in this file format). Putting the word abstract (universally found in academic papers) in quotes means that this word has to be present in all the results.

So, we have attempted to limit ourselves to information hosted by institutions of higher learning, in the form we would expect of a formal research paper. This is useful mostly because trained specialists in the relevant field can be reasonably expected to have looked it over for mistakes or wrong-headedness. Note that is is still easily possible that the information you find is wrong, especially in light of the fact that a paper later proven to be wrong does not erase itself automatically. (“Wrong Persists”) But you will have greatly reduced the amount of information you have to deal with, and the process of choosing what to trust is now much easier.

—

For amusement value, my ever-growing Google News alert for “celiac” is currently:

celiac -cookbook -fad -“support group” -“Pros and Cons” -lawsuit -lifestyle -“gluten controversy”

-Bob

Great write up! Just one suggestion:

In my opinion, one should jump to the methods almost immediately after identifying that paper as what they are looking for. Sure X might be really bad, but the paper might only be focusing on 80 year old patients with renal failure and preexisting conditions. That paper is likely worthless for the person doing research.

Thanks for this excellent article, I just stumbled across it via Facebook. I work in science communication and would love papers to be written in plain English, and properly structured and punctuated. Aside from the scientific terms which people like me can learn, the use of two long words when one short one will do helps keep laypeople firmly on the outside – and inadvertently supports the notion of an ivory tower. But if you can’t explain it simply you don’t understand it well enough, as some clever chap once said. A small point on accessibility: I think links labelled ‘here’ rather than with a page name or description are tricky for people using text readers. Thanks again!

Great advice which applies to other disciplines, e.g. how to order and interpret a body of data or how to configure a process.

Reblogged this on WINNACUNNET BIOLOGY.

Hi! Amazing article! I couldn’t go through it all, but I think you forgot a very important step : making sure that the researchers calculated the necessary number of subjects before beginning the study and how many were actually studied . But other than that the information given is great. This is most of what we learn in med school about scientific articles 🙂

Reblogged this on sea-swoon and commented:

i like this

Fabulous, what a website it is! This webpage presents useful facts to us,

keep it up.