Update (1/3/18) I’ve been overwhelmed with requests for the shorter guide, and the email address below no longer works. So I’ve uploaded a copy of the guide for anyone to download and share here: How to read and understand a scientific article. Please feel free to use it however you wish (although I’d appreciate being credited as the author). I apologize to everyone who emailed me and didn’t get a response! If you would like to let me know who you are and what you’re using it for in the comments below, I’d love to hear!

Update (8/30/14): I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu.

Last week’s post (The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google) sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article. It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article. Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: google “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed. [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals.

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this, then go back to my last post and read one of the papers that I linked to (like this one) and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

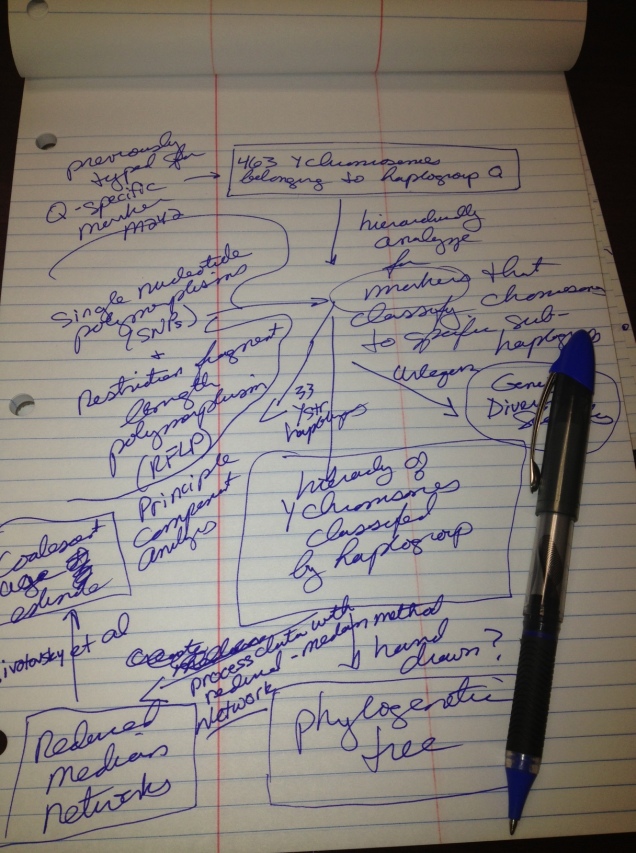

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today (Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q”). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean, just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here, here, and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

THINGS TO PAY ATTENTION TO IN THE RESULTS SECTION:

-Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here.

-If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

-The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

Now brace for more conflict– next week we’re going to use this method to go through a paper on a controversial subject! Which one would you like to do? Shall we critique one of the papers I posted last week?

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example, you can find one here

———————————————————————————————————

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

Do you have anything to add to this guide? A completely different approach that you think is better? Additional questions? Links to other resources? Please share in the comments!

Maybe a full example could help that walks through finding the latest info/consensus on cholesterol and heart disease, sugar and diabetes (versus fat), protein requirements, and a lot of the other contentious topics.

Very good points. That’s a great suggestion, thank you!

Does this include your papers and other mainstream scientists?

I like this site it shows how you lot fudge data!

http://retractionwatch.wordpress.com/

No, none of my papers are in there. I’m a big fan of “Retraction Watch.” It’s a terrific forum for the self-critical process that’s fundamental to scientific inquiry. Kudos to Adam and Ivan for maintaining such a useful resource.

Evolutionary Anthropologist’s Advice: Reject Research Papers if Results Come from Discovery Institute Authors – Evolution News & Views

For the record, the D.I. is correct. Arguments stand on their own merit. To attack the credibility of the authors without addressing their arguments is known as the ad hominem fallacy, and it’s a form of anti-intellectualism. To see Jennifer promoting such a view is alarming.

Also, let me point out that the D.I. is home to many brilliant men and women, many of whom were educated at universities far more prestigious than the University of Texas. For example, Stephen C. Meyer and Douglas Axe, two men who routinely thrash Darwinists in debate, are both Cambridge graduates.

Finally, it should be noted that the D.I.’s authors are no more agenda-driven than any other scientists, they’re simply pushing a different agenda than most. Their agenda is pushing 21st-century biology; Jennifer and her ilk’s agenda is pushing 19th-century biology. Quite frankly, I consider the D.I.’s agenda to be the far more respectable of the two.

Darwin was wrong in nearly every way, ladies and gentlemen. It’s time to let it go and evolve into the 21st century.

I enjoyed that link. I did find it interesting that in a comment in which you claim that the author has a bias, you provide a link to a website which is quite clearly biased as well (On a website which claims to report “Breaking news about scientific research” on evolution and Intelligent design, I was unable to find one article showing evidence which supports evolution published within the last month). Also, may I point out that in the post above it does not state that a paper with a questionable author should be “immediately toss it in the trash.” The way I interrupted it is that you should take note of who the author is and who they are affiliated with. This should be a standard practice for anything you read, not just scientific literature.

For example; There are some scientists who have a history of publishing papers with questionable conclusions. These authors are usually fairly well known to others in their field. This does not mean that all future papers they publish should be ignored, but it does mean that readers should ensure they critically read the papers and evaluate whether their conclusions are accurate.

This seems quite right to me. For example, a great deal of the “pro-ID” research the Discovery Institute touts is from the journal “Bio-Complexity.” The journal’s output seems poor to my layperson’s eyes, but perhaps more significantly their editorial board looks like it was hand-picked to give anti-evolutionary opinions a friendly review: http://www.jackscanlan.com/2010/12/bio-complexitys-opinion-on-intelligent-design-isnt-complex

That does not mean that articles published in Bio-Complexity are worthless or necessarily wrong in their conclusions. But it does mean that a savvy reader should bear in mind that they have probably not passed the kind of scrutiny that a serious, objective journal would bring to bear. The reader should therefore be less inclined to give such authors the benefit of a doubt when it comes to analyzing their methods and conclusions.

The DI’s perennial response to criticisms of their paltry research efforts is to complain that they’re being excluded from high-impact journals. The threadbare nature of their own research publications puts that argument to rest, in my opinion. Rather than serious publications testing (or even proposing) a theory of intelligent design, ID creationists are still banging on about the second law of thermodynamics and entropy: http://bio-complexity.org/ojs/index.php/main/article/view/BIO-C.2013.2

It’s possible that such inane arguments are being excluded from serious scientific publications because of some terrible bias. It’s also possible that those arguments are simply so silly and wrong that they don’t rise to the standards of well-regarded journals. One of those possibilities is much more likely than the other.

“The DI’s perennial response to criticisms of their paltry research efforts ”

Can you document an instance of their paltry research efforts? Or is this just your opinion?

Yes, of course I can. It only takes a few seconds of Googling to find plenty of instances of “paltry research efforts” that are touted as being significant to Intelligent Design, but utterly fail to actually make discoveries.

I’d point firstly to their pocket journal “Bio-Complexity.” I am not a scientist, and not very familiar with the standards of scientific publications, but I am fairly certain that serious scientific endeavors (especially ones that are well-funded and supported by at least one private think tank) produce more than two research articles a year. In all of 2013, Bio-Complexity didn’t manage to publish a single research article. The few articles they have trickled out have been ineffective–the only people who seem to take them seriously at all are other creationists searching for validation.

I’d also point out the history of failed ID journals. There are several, whose rather sad histories are documented at http://ncse.com/book/export/html/6703 (under “The History of ‘Intelligent Design’ Journals”). These journals typically fold relatively quickly, in my opinion because they don’t have any serious or respectable research to publish. They also failed to make any impact on non-creationists. By and large, serious scholars have yet to find anything of value in these agenda-driven journals.

The ID journals don’t even seem like they’re trying to generate serious research anymore. They seem, instead, like an effort to create a veneer of respectability. That’s certainly how Casey Luskin used them in his hit piece–rather than citing to any actual *results* or discoveries that ID “researchers” have generated, he just pumped out a laundry list of PR pieces intended to create an impression that there must be some kind of meat in there, somewhere.

A good example of this is the “Cornell Origins of Biological Information” conference that the preeminent ID blog Uncommon Descent has been flogging for some time now. Every time the conference is mentioned, they’re careful to call it “the Cornell OBI Conference.” They desperately want readers to believe that a respected academic institution (as opposed to a bible college like BIOLA, which may have great programs in some fields but has no scientific credibility) has sponsored some ID research.

In fact, the “Cornell OBI Conference” wasn’t sponsored by Cornell University. It was held in a rented room at the Cornell School of Hotel Administration, which rents facilities to private parties. This like a scientific conference calling itself “The Marriott Conference on String Theory” because that’s where they rented some rooms. As far as I can tell, that doesn’t happen. So why latch on to the Cornell name? Because they know readers will interpret it as a sign of scientific credibility. Rather than earning that credibility, they’re trying to sneak it in through the back door.

ID seems to be unable to produce real research data, and unwilling to even try. They spend a great deal of effort, though, on trying to build the *appearance* of scientific legitimacy. This is why ID is often called a “cargo cult.” (Please Google the term if you’re not familiar with it.) I think it’s fair to call a research program that has failed to produce any meaningful results, and seems focused more on creating the *appearance* of solid research, “paltry.” At least.

I think that’s demonstrates an important value to this piece on reading scientific papers for laypeople. The Discovery Institute, in its insecurity, has invested an enormous amount of money and effort in building a hollow research program–one that is intended to *look* legitimate, but has no real depth or empirical discoveries to its name. Laypeople have a hard time distinguishing substantive research pieces from fluff. Hopefully this will arm laypeople to see through the DI’s smokescreen to the yawning void at the heart of their “research” efforts.

agreed

Jennifer,

It is interesting how someone as smart as you can be so small-minded and, to put it mildly, tacky. You take a disingenuous, unnecessary swipe at the folks at the Discovery Institute when in fact, you know that their scholars graduated from PhD programs at schools far superior to yours (such as Cambridge and Princeton). So you end up looking very small and though you’re from a great school, you honestly can’t say your scholarship is somehow superior to that of the DI scholars who have PhDs from highly respected (even better) institutions just as you do.

Now what is fallacious about your statement regarding DI having an “agenda” is that they don’t have any more of an agenda than you do. Your agenda is metaphysical naturalism, which is the a priori view that there is nothing more than natural causes that can explain the natural world. There is nothing more dogmatic and closed-minded than that position. All the DI folks are arguing is that the Darwinian paradigm of natural selection acting on random variations cannot deliver the complexity and diversity that we see in the natural world. Pretty simple. Clearly, they believe there is agency behind the increasingly complex life we have seen over the epochs since before the Cambrian explosion. And Darwinian evolution does not even address the Origin of Life question. So perhaps you have a clear explanation that the rest of us aren’t aware of.

I want to use a simple example to demonstrate the fallacy in your reasoning. When a person is found dead, police investigate if the death is due to natural causes or if there is some type of foul play. If the death was not of natural causes, then either the cause of death is self-inflicted or someone committed murder. In the cases of self-inflicted death or murder, the police can come fairly quickly to the conclusion that some sort of agency was involved, because all of the clues point to it. So making the determination that there is agency while not knowing who the agent is takes place all of the time. Likewise, the reasoning of the DI people is when you look at the complexity of life, there are signs of agency because of the high volume of information and design that would be required to create something of such complexity that couldn’t be achieved on a step-by-step basis through random variation and natural selection (particularly given such short time frames). In other words, we see discontinuous jumps in information throughout the fossil record. We see appearance, stasis, and extinction in the fossil record, and we do NOT see gradual increase in complexity. So to say there is probably agency is at least a reasonable conclusion, even though that entirely reasonable conclusion is reviled and derided by you.

My suggestion is that you stick to being a research scientist, as you’re not on par with the philosophers of science at DI. You’re not trained in it and you’re obviously not good at it. And the researchers they have at DI are every bit as good as you with the PhDs to show for it from schools, again, there are every bit as good as yours if not better.

I note that the DI defenders start by decrying ad hominem attacks and launching an… ad hominem attack. Doesn’t matter what school she went to, her arguments stand on their own merits.

I haven’t read Walter’s post, but at no point did I decry ad hominem attacks. In fact, I quite enjoy them. What I did decry, and what I do abhor, are logical fallacies. Tell me, DaveH, can you distinguish between an ad hominem attack and the ad hominem fallacy?

I don’t feed trolls beyond a bite to tease them.

Translation: “No, no I do not.”

Exactly as expected.

And by that he means, “I don’t understand it, so it can’t be. Since it upsets my view of the world, it musn’t be. And that makes anyone with (literally) mountains of evidence to the contrary… wrong, and stupid. Pretty Simple.”

oops. That was a snack for the troll, wasn’t it.

Your analogy to criminal forensics is both false and inapposite. It’s false because if forensic investigators can’t determine a natural cause of death, they don’t immediately assume that an “agency” caused that death. This is the fundamental logical flaw in the so-called Explanatory Filter. (You can read a thorough debunking of the flawed reasoning behind the filter here.) It’s inapposite because when forensic investigators do conclude that an “agency” was involved, they do it by comparison to known agencies using known methods to achieve comprehensible goals. None of those things apply to the “designer,” which (if it exists) acted in ways that are totally incomprehensible to human minds.

You are certainly correct that Jennifer is not on the same level as the “philosophers of science” at the Discovery Institute. Unlike the DI staffers (particularly Casey Luskin, a layperson with no particularly relevant scientific training, credentials, or accomplishments to his name), she is producing relevant research and engaging productively with the scientific community. The DI’s “philosophers of science” are not actually engaged in any sort of objective endeavor to improve science or human knowledge; they are, as the DI’s own internal documents showed long ago, part of a self-conscious effort to prevent empirical science from eroding sectarian religious preconceptions.

That link isn’t working for some reason – it should point to http://theskepticalzone.com/wp/?p=2592

“The DI’s “philosophers of science” are not actually engaged in any sort of objective endeavor to improve science or human knowledge; ”

Let’s just ignore their arguments, even though they are very compelling. After all, we don’t want the truth to get in the way of science.

This assumes that those arguments *are* compelling. But those arguments seem to only be compelling to people who share the DI’s religious roots and preconceptions.

In the marketplace of ideas–specifically the scientific community, which subjects ideas to rigorous empirical testing–the DI’s breed of creationism has utterly failed to make any headway. I can’t think of a single piece of evidence that Intelligent Design explains more effectively than evolutionary theory does. IDists would obviously disagree, but they can’t do what an evolutionary biologist can: point to an enormous and productive body of research growing out of the more empirically-supported theory.

It might be that scientists reject ID because they are members of a shadowy global conspiracy dedicated to covering up the truth of Intelligent Design. Or it might be that the DI is just wrong. Given the enormous disparity in actual output (and the score is something like “Objective Scientists: 1,000,000,000, Cryptocreationists: 0), I think the second is more likely.

You seem to disagree. What’s your explanation, then, for the total failure of the ID community to generate any empirically verifiable discoveries or research results?

in spite of some personal opinion, this is a good guide.

Reblogged this on physician21.

thaaaaaaaaaaaaaaanx

vvgjggh

Jennifer,

Is your approach of trashing dissenting viewpoints really a good scientific approach? Sadly today it is presented as such. The effort to maintain Darwinian orthodoxy hearkens back to Inquisition and the persecution of Galilleo . You really can’t see the irony in your refusal to consider anything that is outside of orthodox dogma? Science ceases when dissent is not allowed.

Mike Nelson

Dissent and dogma are not science. You wanna’ have your ideas accepted as science? It’s simple:

A) Learn everything there is to know in the field, understand the areas of controversy and directions of new research, design good experiments, fight for the funding, do the experiments, collect the data, do careful analysis, assume you fooled yourself so seek advice/criticism/counsel, write the monograph, get it rejected many times, do the edits, publish the article, wait for the wider criticism, have your data and conclusions upheld in replication.

B) Repeat (A) until you are sorry you ever thought about it.

C) After 20 years, have your family ask, “What is it you do again?”

“you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings” – very well put. Communication of Science and Scientific Research results has very precise language and nothing is arbitrary or trivial. I have been stressing this aspect of doing science to all my colleagues, but they are never serious about it. Nothing, in Science, should be taken casually.

Thanks, Jennifer.

This works for science editors, too, especially as a resource early in the career. Taking the time to apply this approach to a few articles — self-education time, after the journal deadline has been met — will sharpen instincts for sound editing over years and years to come. Peer review should be enough, but a scientific journal’s copy editor often serves as the last check for errors in reporting: undefined terms, contradictions between text and figures or tables, and of course missing or sloppily defined significance. THANK YOU!

PS: I keep an almanac of things I’ve learned or looked up, so that I don’t have to dig for the same enlightenment again and again: specialized vocabulary, usage examples, classic references, equipment and manufacturer information, and URLs for reliable databases and international standards. I recommend the same to grad students.

Thanks so much! The process definitely gets easier the more one practices. Your almanac idea is a good one.

What a great article. I’ll be taking all this advice on board when I start my MSc in a couple of weeks time. Thanks very much!

Also, a link to PLOS maybe wouldn’t go amiss so that people can see some good open access papers.

Sorry to keep posting separate messages, but would you mind if I linked to this article from my blog? I think it might really benefit some of my readers. (Once I’ve actually found a reasonable number!)

Please feel free! Thank you for your kind words.

I wish this guide had been available during my undergrad days when my professors tortured us with paper after paper! Of course, I am so glad that they taught us this skill before grad school…

I didn’t make it through all the comments, so I hope my extra input here is not too repetitive. I just wanted to point out that the average person does not have access to Web of Science if they are not affiliated with an institution that has a subscription. I recommend using the advanced feature within Google Scholar to search for papers, and the results visually display whether the paper is available online for free. Of course, Google Scholar has a low stringency for searches, so readers must be sure to sort through the results and ignore any “junk” hits.

I look forward to reading more of your articles!

Thank you very much!

In today’s world and the popular (and often confused) debates of the minute, an article such as this explaining scientific literature and how to interpret it is so very timely.

Thank you for this… so very informative.

Read the article with great interest. This will be of great use communicating with decision makers in developing countries who often have to make judgments based on scientific articles and/or other peer reviewed publications. Thanks!!

Thank you so much! I’m delighted to have written something helpful.

Reblogged this on Socio-Economics, Biosafety & Decision Making and commented:

The following is a step-by-step guide to understanding scientific papers published in the blog :”Violent Methaphors”. I hope that you take the time to read this paper especially if you do not have experience reading this type of articles. Part of the issue that will be of interest to decision makers and regulators in developing countries while examining this type of evidence for biotechnology and especially with regard to GMOs, will be the ability to judge the quality of a specific paper and of a collection of papers, which constitute evidence responding and in some cases supporting research questions, hypotheses and interpretation. Cheers to the blogger for a quiet neat document!!!

After a lifetime of reading scientific papers – the advice I would give is:

If you can’t understand the abstract, or if the abstract does not make you want to read the rest of the paper then forget it. Really good papers shine out and tell you that there is something really worthwhile at the beginning. If the abstract intrigues you then it is worth reading the rest of the paper. When you find a good paper about something which really interests you then read it carefully and look at the methods section especially. Understanding methods is what makes a good scientist, and understanding when methods are inadequate is crucial. When we examine PhD students it is understanding of methods which determines whether they pass or fail. The discussion is always interesting – they are trying to sell you a story. It’s a pitch to tell you how important the work is. But very often they try to oversell the story, making assertions which are not justified by the content.

But the most important thing is, if you are writing a paper – please make it readable – the best advice I was given was imagine you were telling the story to a friend at the local bar- the friend is a scientist but not working in your area.

Thanks for the blog – really liked it and the comments

Thanks for your comment! I agree about how crucial understanding methods is for young scientists. And that’s great advice regarding how to write scientific papers…I’ll try to follow it myself!

Interesting read — would make an adjustment to the second paragraph eluding to a bacterial infection when referring to measles.

Ugh, thanks for catching that!

No problem. I’m not a big fan of vaccines and I use many of the same principles you stated above.

If you want to save some trees I’d also suggest using a free program like X-Mind for drawing diagrams. 😉

my boyfriends notes looks like that

Am currently undertaking a literature review for my psychology PhD thesis and found this article extremely helpful. Really appreciated the very clear steps to follow at each stage as I have so much literature to review it can sometimes be mind boggling as well as very anxiety provoking. Have you written anything on steps to follow when reviewing a review paper Jennifer, or could you say anything briefly? Many thanks

That’s very well written 🙂

I don’t know if it’s just me or if everybody else encountering problems with your blog.

It appears as if some of the text on your content are running off the screen.

Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them too?

This may be a issue with my web browser because I’ve had this happen

before. Cheers

In response to the “Several people [who] have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, ….” please note that all papers reporting on research that was supported by a grant from any of the National Institutes of Health must be made availeble on PubMeb, whether they are published in biomedical or in non-biomedial journals. So, for example, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20160984 is the PubMed publication of a paper on speech patterns in children with autism that was published in the journal “Speech Communication”.

Found this extremely interesting and helpful. Wondering if anyone could suggest two papers to use to evaluate this. I’m looking for one that would present some findings on evolution using the fossil record and one that is more molecular / DNA based. Nothing too confusing as I’m an amateur (hack).

Click to access 60b7d52d76411f30ff.pdf

I am currenty reading and studying this research paper, although I find it difficult to understand.