Update (1/3/18) I’ve been overwhelmed with requests for the shorter guide, and the email address below no longer works. So I’ve uploaded a copy of the guide for anyone to download and share here: How to read and understand a scientific article. Please feel free to use it however you wish (although I’d appreciate being credited as the author). I apologize to everyone who emailed me and didn’t get a response! If you would like to let me know who you are and what you’re using it for in the comments below, I’d love to hear!

Update (8/30/14): I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu.

Last week’s post (The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google) sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article. It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article. Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: google “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed. [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals.

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this, then go back to my last post and read one of the papers that I linked to (like this one) and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

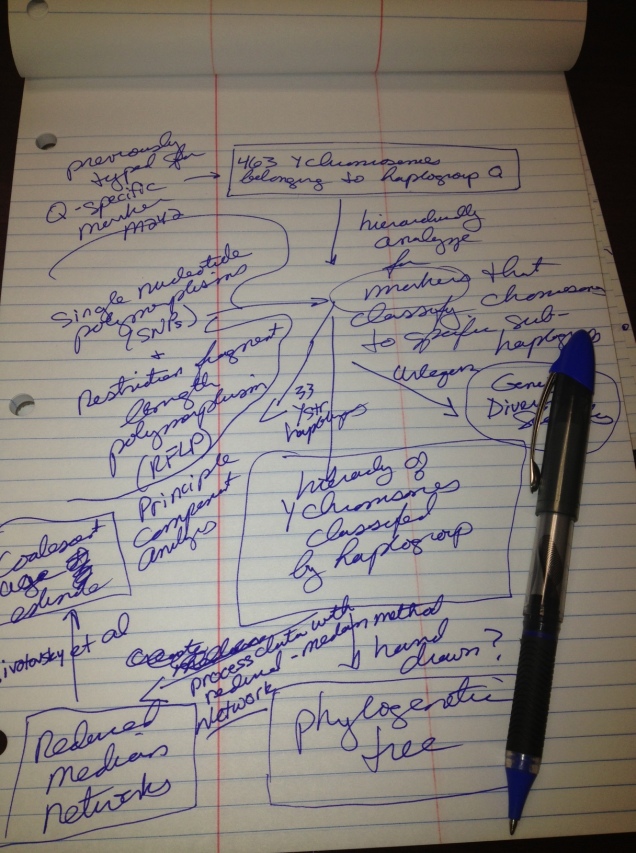

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today (Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q”). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean, just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here, here, and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

THINGS TO PAY ATTENTION TO IN THE RESULTS SECTION:

-Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here.

-If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

-The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

Now brace for more conflict– next week we’re going to use this method to go through a paper on a controversial subject! Which one would you like to do? Shall we critique one of the papers I posted last week?

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example, you can find one here

———————————————————————————————————

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

Do you have anything to add to this guide? A completely different approach that you think is better? Additional questions? Links to other resources? Please share in the comments!

This is very interesting and I have downloaded two articles you recommend on interpreting statistics.

But I believe that most people, most scientists even, read the Abstract before the paper. I kinda imagine most people read the Abstract to decide whether they want to read the paper at all (especially if they have to buy it). That’s why it is the first thing presented, sometimes even on its own page.

While these all seem like worthwhile recommendations, I doubt that even the positive commenters go through such a rigorous drill on papers outside their field.

Those who actually take the trouble belong that rare, semi-mythical tribe who brush and floss after every meal, put on sunscreen every day, and don’t step on any cracks ’cause it breaks your mother’s back.

I actually only read the abstract to decide if it is a paper I want to read. I am pretty rigorous in reading papers, but I always look at the figures first and find what they are talking about in the paper and make notes in the margin about the figures before I start reading the paper because a lot of times I find out then if it is really a paper I want to read. If it is a paper I want to read I go back and look at those figures dozens of times while reading.

In case of a paper on a medical trial, I’d also suggest looking up the trial in the trialregister(s). (like http://clinicaltrials.gov/) This way, people can check whether the ‘true’, pre-specified primary outcomes are described in the paper.

Excellent evolution of Critical Analysis Jenny!

BILL!!!! All credit goes to you 🙂 Email me! jenniferraff@utexas.edu

The first question I ask is “cui bono?”. If the narrative fits one particular agenda perfectly, the funding filter may be in effect. Best to see how it plays dumping cliche assumptions and see how it holds together.

You left out one key section to pay attention to: the References. When I read a technical paper, I identify the authors, read the introduction, then go to the references to see who and what is being referenced. Then I move onto the conclusions and then back to methods.

In my own field, I am very familiar with the various schools of thought out there, so I can usually immediately tell from the references cited how the authors are viewing the issues and whether or not they are leaving entire approaches out of their analysis. In area that I am unfamilar with, I can usually quickly Google the topic and come up with a bunch of information to tell me about the various different approaches researchers are taking in this particular area.

Over the years, I have found that many papers intentionally or unintentionally omit alternative approaches from other schools of thought that could lead them to different conclusions. In my opinion, we have finally solved defined problems when you can come up with the same answer when you look at the data through multiple lenses.

References are definitely important (and I mention them in my last step). However, I’m not convinced that the average casual reader will necessarily recognize that a critical reference has been omitted. IMO, that’s an obligation for the reviewers.

It’s a good guide, although I agree with the commenter Geoffrey about reading the abstract before everything else to give you an idea on whether the paper is even relevant to what you’re looking for.

Also, while it’s a lovely guide for those people who have the time, rigour and intellectual discipline to go through all the steps, I strongly doubt its usefulness for the ‘layperson’. Laypersons don’t have the time, they don’t want to google every single word they don’t understand, and they don’t want to draw diagrams to figure out how the experiment was done. And, assuming they are complete novices to the field, they also won’t have enough background knowledge to answer quite a few of the questions posed, such as the peer opinion one. However, if they are actually interested in all those things, you probably can’t call them lay.

Instead, these people who don’t read papers on a daily basis want to know why scientists are doing this research, what their conclusion is, whether it is reliable and how it affects their life or the world, or future. And maybe a little about how it was done, but without having to interpret technical jargon. Mind you, it’s not because they are lazy. But, as you note yourself, they are novices and not trained to do this, and probably have a day job, a family and some hobbies to fill their free time with sufficiently.

And that’s why, in my opinion, instead of teaching the general public to read scientific papers (to which they often don’t even have access to anyway because of paywalls), scientists, journalists and science communicators at universities should put more effort into explaining the papers to the people who don’t have the time to read and google the terminology and methods.

Absolutely agree, there should be way more transparency!

I agree with your last point and am working on it! 🙂 However, I’ve gotten enough specific questions from readers who want to know how to understand primary research articles that I felt some kind of guideline was needed.

PubMed is different from MEDLINE. Journals can now get into PubMed simply by adopting an open access business model, which usually involves authors paying to be published. MEDLINE is a more stringent index that involves a review committee vetting the quality of journals that apply to be indexed. MEDLINE-indexed journals have passed a quality test. PubMed-indexed journals may or may not have passed this test (MEDLINE journals are included in PubMed, to add to the confusion), but not all PubMed journals have gone through the process required to be indexed in MEDLINE.

I’m sure Kent doesn’t want to give the misleading impression that it is only open access journals that get included in PubMed without meeting the Medline test. Kent is probably referring to PubMed Central, a database that he is particularly interested in. A recent analysis found that a range of journals, both traditional and innovative, had manuscripts in PubMed Central, with some manuscripts dating back to the 1960s http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3066581/

Congratulations Jenny for the excellent article. It certainly helps the people that are still trying – having no scientific background – to understand who is who in our crazy an polarized word. I get shivers down the spine every time i think that people with no (or very little) knowledge about some themes like modern science have power to legislate about it. Vaccines, abortion, euthanasia, cellular research and so many others.

Providing a way for the people to better understand a complex issue is a very noble goal. It’s a pity so many people will find “too much work to do” and will keep using Google or Yahoo answers to fight for a crazy idea.

Again, thanks for dedicating time to improve the world.

Veybi

Thank you!

An excellent description of how to exercise scrutiny when reading. Thank you. I wish I had this guidance when I was beginning my college education in the biological sciences back in the early 1970’s. The funny thing is, this was basically how I was taught by a professor of mine, now long forgotten.

I do have a point of clarification that I know was not intended by you but could be misinterpreted by some.

you said: “Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school”.

Some could be misinterpret this sentence as implying that those reading skills are not really learned by undergraduates. There are a few folks who only have a Bachelor of Science degree and are fairly good at reading and understanding research.

Can everyone understand the hydrophyllic versus hydrophobic differentiated function of a cell wall non-specific pore? Not likely, but science nerds do exist that do understand the differentiated function of non-specific pores as well as the difference between static soaring and dynamic soaring in birds.

Science nerds unite! our species depends on it!

Hm, yes, I hope it isn’t interpreted that way. It’s not typically a course that’s taught to undergrads at the universities I’m familiar with, but it should be!!!!

When I was in school it was just expected of us to attempt to master as undergrads. To pick our professors’ brains all the time and to exceed expectations as much as our limited skills would allow.

The rigor with which undergraduate students were challenged by the faculty of College of Natural Resources and Sciences at Humboldt State University, still resonates with most of us today, 35 years later.

Institutional exceptions do exist, not all universities wait until you are a grad student to begin honing these more sophisticated critical thinking skills. I think for us, being physically separated from the remainder of the state of California fostered more self-reliance on the part of our professors back in the 70’s which has carried over to today.

Reblogged this on The Smell of Evolution and commented:

Nice blog on critical thinking when reading scientific papers!

This is a very interesting piece of article, and a helpful one at that. I would say, this only is a guideline for non-scientist but budding ones as well.

For me, abstracts totally help me get the immediate gist of the whole scientific process- problem-hypothesis- results etc. that would help me understand the context of the paper. It, should not be too offensive to begin with those so long as you take up the paper and really read through it.

Small correction! I’m not a professor (yet). Just a research fellow 🙂

That’s as may be, but you are definitely one hell of a teacher.

Great article, and, yes, understanding how to read and interpret the literature is key to empowering yourself as a patient (in clinical medicine) and as an observer of the process of science. In my experience, peer review does not guarantee quality, as you are aware, and the only way to know the state of science is to read science, not reporting on science, and to read it critically.

Here is a self-promotion alert: I published a book on how to read scientific literature critically, and have blogged extensively about these very issues, though have not been an active blogger here in a while.

http://betweenthelines-book.com

http://evimedgroup.blogspot.com

Reblogged this on riccieclayderman's Blog.

I read a few papers every year. Not because I am naturally slow, but because that I am doing what you are describing at an unconscious level. My background is in electronics and in school we had to learn the six steps of troubleshooting as well as transistor theory backward and forward. Working through faults required no less than a three page description of testing, discovery, planning, recommendation, procurement and finally, correction.

Qualifying submarines was also an education in cause and effect.

You have added to my ability to glean knowledge from that which I read.

Reblogged this on amytang0 and commented:

Useful for interpreting research papers. Sometimes I find myself just running straight to the abstract, and I need to stop that.

Great read

I usually read in the order abstract-introduction-discussion-results-methods. I generally find it very difficult to understand the results unless I have seen the discussion first, and in many cases I’m not interested enough in the details so spend all the time needed slogging through the results. In my own papers, I’ve always tried to write the discussion sections so that a reader can understand them without having read the results first.

Good post – an important topic! I spend a lot of time talking to undergraduates how to read scientific papers, and even though they are ‘scientists’ (or at least scientists-in-training), your advice is solid. Never read the abstract first is SO important for all of us. IMHO, Abstracts are often weakly constructed, and (frankly) boring to read! (my own included haha)

What your post (and many of the comments) point to even more is the need for authors of ALL research paper to also write a plain language summary (e.g., here’s my post on the topic) http://arthropodecology.com/2012/11/08/science-outreach-plain-language-summaries-for-all-research-papers/

Just imagine how much further ahead we would be if scientists could learn to write in a jargon-free manner that explains not only “what” they did, but also the “how” and most importantly, the “why”.

…And training to write these is needed, my ideas on that, are here: http://arthropodecology.com/2013/08/01/a-guide-for-writing-plain-language-summaries-of-research-papers/

Thank you! I couldn’t agree more about the plain language summary. Definitely going to start doing that with mine. Appreciate the link.

I am not sure that the researcher him/herself is such a great person to do this — it will not be unbiased, that’s for sure. We all get into our own cognitive corners and will defend our biases tooth and nail. Nothing replaces being able to unravel the mysteries of a paper on your own.

Right – I think the reader, ideally, could read a plain language summary first, as written by the author, and that could help guide the reader as to whether the work is interesting / relevant, and whether the reader ought to delve deeper into the topic. If so, the reader can get the original article and read, as per what this post suggests. I think a plain language summary provides a broader overview that would be jargon-free and give everyone an easier road towards accessing scientific literature.

Maybe it’s beyond the scope of this post, but I think that, while reading the methods section, you consider the research design. After a quick glance at your CV, most of your work involves recruiting available “subjects” where subject characteristics (such as geographic origin) determine the primary comparison. That’s perfectly appropriate for many kinds of studies in fields from anthropology to epidemiology. In studies comparing the relative efficacy of treatments, a randomized design might be more useful, particularly for a study trying to definitively settle the question. The issue is whether the researchers have done enough to control for other unrelated or uninteresting sources of variation, beyond the question at hand.

Of course, “observational” and “randomized” are terms, each with their own respective technical cans of worms.

Thanks, too, for calling out the importance of statistics (my career) and even bringing in a little statistical jargon (“reduced median method)! It’s usually not important that typical researchers understand the detail of the stats, but, yes, they should get the gist of it.

Great post.

Here’s a great paper on “surrealistic mega-analysis of redisorganization theories” published on Pubmed: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1299350/ – Very funny. Worth a read.

That is freakin’ hilarious!

Right up there with “Eschewing Obfuscation.” Should be published in a science special from The Onion.

Read the entire article learned much and apply the following applications as so:

-Bookmarked, “Web of Science.”

-Indeed the abstract alone may not constitute the primary study of the particular research.

-Learned to identify agenda driven paper vs. unbiased scientific documented facts.

-Always ask more questions!

Currently attending college and studying to be a lowly plant scientist (Horticulture… a wanna be farmer/gardener). At first I thought, yeah, this is going to be easy. Slap some seeds in the ground, apply the right substrate, and watch it grow. There is definitely a science behind it, much like all biological organisms that reproduce to survive. Horticulture is no where near the scientific “brain power” in comparison to Botany or Ethnobotany.

Thank you for the informative information!

Reblogged this on DIGIT.ME.

Thanks for doing this. I would especially emphasize in point 7 the importance of figures and diagrams. Much of the writing in a paper is just a retelling of the figures. Sometimes the authors’ interpretations will differ from one’s own. Also, for students, I tell them they should consider what exactly had to be done to get the data for the paper. This gives them an idea of how much work they have to do to get a paper out.

Very interesting post! I’m glad it was freshly pressed so it could be brought to my attention, congratulations on that, by the way!

I have a slightly different approach and, with all due respect, I don’t entirely agree with you on reading the abstract until the end (additionally, I’ve heard of people who don’t read the conclusions either so not to get biased). When I have to do some lit search, the abstract helps me decide whether the reference is relevant to me or not in a much quicker way than reading the introduction. In fact, if I’m performing the lit search on a topic related to my research I don’t really pay too much attention to the introduction (I’m already sold on the project! I don’t need to read why it is relevant/important/interesting), but I do understand your point and I realize your post is addressed to laypeople. I guess I’m reading papers in a bona fide way, hoping abstracts are well written according to the work. Unfortunately more and more papers nowadays are not well written not to speak about how many frauds have been spotted recently.

This is getting too long, I think I better post my own insights on my blog 🙂 Thanks for sparking this interesting conversation; I’ll make sure to follow your blog from now on.

Best wishes

When I teach “article reading” to undergrads, I also make sure they understand the purpose of each piece of the paper, including the title, so they know how to critically approach each piece (e.g., the title highlights variables and research design [at least in psychological papers it does] the intro portrays the broad purpose and situates the argument within the existing literature, the method lays out the steps taken to test the hypothesis, results explicate the hypothesis testing process, etc). With such meta-knowledge my students remark that the process of reading primary sources becomes less daunting and more manageable.

When directing a discussion about science literacy to the general public though, I find its not their ability to properly digest a scientific paper that holds them back from benefiting from the exercise as much as their attitude (or understanding) about the scientific process. That is, non-scientists are so used to “going with their gut” and following their emotions and intuition that they take a scientific perspective or finding and dismiss it if they don’t like it, or, as happens often with psychological research, if they can think of one case that counters the finding, they claim that their friend/child/parent/or self disproves the science and they ignore it. In other words, its their naivety about the process of science and theory building that interferes with their ability to gain anything at all from reading the research. When they don’t know the scientific definition of a theory (and the science that goes into building one), they approach a discussion of research outcomes not from a standpoint of “what does this science tell me about my behavior” but rather, “does this science match my experience?” If “yes,” they believe the study is good and valid, and if “no” they claim the study is flawed and invalid and all that comes from it is pure conjecture.

As another commenter noted, scientists have a ways to go in terms of educating the public on how to use their findings. Your post is a good start though – do you plan on writing additional how-tos? I’ve taken a different aim with my blog and am writings posts with the purpose of applying research and theory to everyday situations.

Congrats on getting freshly pressed. Its fun to find other like minded educators in different disciplines out there in the blog-o-sphere.

Many think that just because they are referencing the abstract they have absorbs the research.

Reading the abstract only beats reading the condensed second hand news article on some source like Yahoo. When I find an article about some recent research I almost always tried to find the actual paper. However, lot of them are locked away behind a pay wall, and we are left with the abstract.

Two thumbs up!

Really great explanation about how to tackle scientific papers – thanks!

This was very well done and I hope you don’t mind if I use it for my undergraduates!

I guess I too question exactly how many lay people will find this useful in a practical sense. However it is correct and perhaps its best value is to indicate that science takes time to understand well, and that at many cases you have to start at the beginning. I would say for something who didn’t know anything about a topic that getting some basics from a textbook would be a better starting point before tackling papers which start to address the leading questions in the field. As an atmospheric scientist I see the climate change deniers all the time making all sorts of unscientific comments that demonstrate their lack of understanding of fundamental physics let alone the climate system. The truth is you can’t learn about it through articles in the media. I feel that if you don’t have the time or the energy to really understand the subject then perhaps you should be willing to trust the people that do. The scientists. Not special interest groups, politicians, celebrities, etc.

Reblogueó esto en Mariusy comentado:

Add your thoughts here… (optional)

Reblogged this on Not yours.

Reblogged this on 紫木蘭 and commented:

Awesome and incredibly useful! 😀

Thanks for an excellent attempt. I fear, though, that in some subjects, original papers a can never be comprehensible to people with no background in the subject. Even in biological sciences, the details of mathematical and statistical arguments are going to be hard going for a non-mathematical reader (especially, perhaps, when they are written by authors who themselves have a weak background in mathematics and statistics).

The advent of critical blogs as really helped, but of course the problem then becomes which blogs you should read. I suspect that most people can recognise critical writing when they see it. The danger is that they pick blogs that agree with their own prejudices.

Important “reminder” to scrutinize research papers with a suspicious eye. Checking the “References” cited is key. — even applies to reading blogs.

Very nice and thorough. The only problem is… reading a paper like this will take a day. A graduate student might have the luxury of taking a day to really read a single paper, but most of us have a stack to go through and about 4 hours (if that!) to do so.

So, here’s the abbreviated method I use:

* Introduction. Skim prior work to look for unfamiliar citations. If you have been around for a bit, you’ll know “the usual suspects”. If all are unfamiliar, skip for now, not worth the time (yet)

* Results (yeah — skip the methods for now) — did they say something interesting or unexpected? If not, paper goes in the trash.

* Having finally found a paper that’s actually worth reading (and tossed 60% of the pile), skim the methods. If things make sense, move on and double-check conclusions. If something “doesn’t compute”, start digging. At this point, it’s actually worth spending time on the paper.

* If everything checks out, you have already learned something new. Now go back to the introduction and go through the references. You will quite possibly learn a few new things as well.

* Depending on your level of excitement, you might allocate a few more hours alone with the paper. Definitely worth the time.

Reblogged this on setariaviridis.

Wonderfully written. I am a biotechnology student and i can identify with your post as i have faced these problems quiet a few times. Now i know what i have been doing wrong. Very useful article!

Thank you so much! I’m delighted to have written something that you find helpful.

I ll look forward to your posts!

Articles like these are badly needed. However they point out the main problem that exists today with social media and the rampant debates that occur on every conceivable topic in the forums and comment sections. Learning detailed science research and understanding stats is too much work and too difficult for the average person, who may be also fairly busy in their lives. So we tend to take shortcuts, learning from blogs, tv, and books ie other authorities. But we may also filter them based on our present beliefs (see The Believing Brain). For example I lean heavily vegetarian (now plant based no oil) and recently gravitated to Dr. McDougall, Dr. Barnard, Esselstyn, etc and the science seems compelling, whereas others gravitate to Paleo and Wheat Belly authors so they can continue to consume meat, dairy and oil.

And there are so many apparent contradictory findings (coffee is good/bad, coconut oil, etc) that people are left confused. Certain people have even tried to debunk the China Study or lipid hypothesis. You end up having to trust the authority more than the science to some extent. And these studies are often statistical in nature and only involve surveys. “Are you fat?” Yes. “Do you sit a lot?” Yes. Therefore sitting is bad.