Update (1/3/18) I’ve been overwhelmed with requests for the shorter guide, and the email address below no longer works. So I’ve uploaded a copy of the guide for anyone to download and share here: How to read and understand a scientific article. Please feel free to use it however you wish (although I’d appreciate being credited as the author). I apologize to everyone who emailed me and didn’t get a response! If you would like to let me know who you are and what you’re using it for in the comments below, I’d love to hear!

Update (8/30/14): I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu.

Last week’s post (The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google) sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article. It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article. Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: google “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed. [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals.

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this, then go back to my last post and read one of the papers that I linked to (like this one) and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

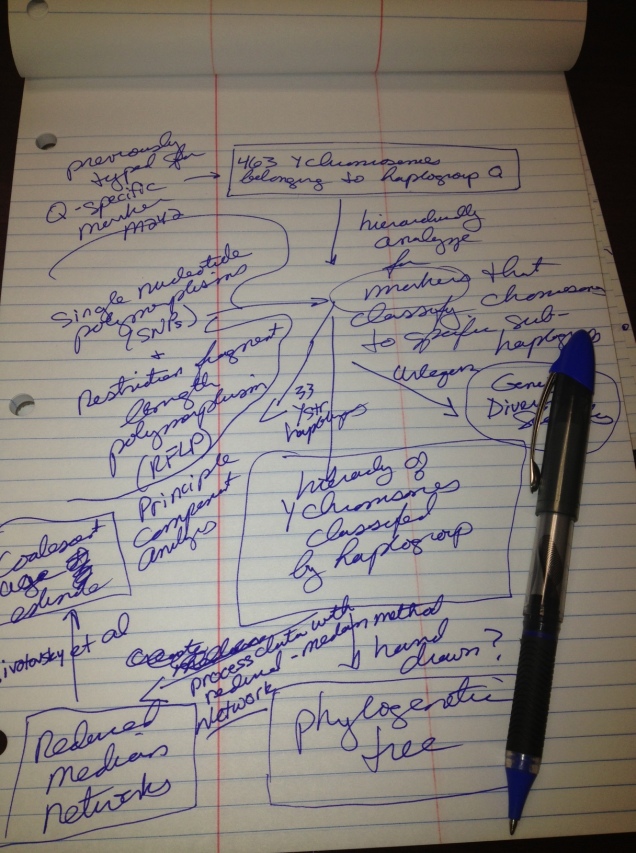

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today (Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q”). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean, just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here, here, and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

THINGS TO PAY ATTENTION TO IN THE RESULTS SECTION:

-Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here.

-If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

-The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

Now brace for more conflict– next week we’re going to use this method to go through a paper on a controversial subject! Which one would you like to do? Shall we critique one of the papers I posted last week?

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example, you can find one here

———————————————————————————————————

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

Do you have anything to add to this guide? A completely different approach that you think is better? Additional questions? Links to other resources? Please share in the comments!

Excellent! I’m going to use this on my class

Excellent article! The only thing I would add is that make sure the abbreviations in a paper mean what you think they mean. More than once I’ve been fouled up by one abbreviation meaning two or more things, especially when the paper crosses a couple of fields.

That’s a terrific point. I also had a lot of trouble switching between papers in different fields (my research is very interdisciplinary) until I became more experienced with such things.

I came across a few other useful descriptions of How to Read a Journal Article:

http://psychology.about.com/od/psychologystudytips/p/read_articles.htm

http://unilearning.uow.edu.au/reading/1d.htm

http://www.sagepub.com/ballantine2study/read.htm

http://library.guilford.edu/guilford-college-writing-manual/college-level-reading/reading-a-journal-article-critically/

Thanks for those!

This is outstanding– and not just for non-scientists. I’m going to make it required reading for our anesthesia residents during their (required) research rotation. Thank you!

I would suggest you critique the Wakefield paper-and the sequelae. Its certainly raised a controversy and has a lot of subsequent literature.

I’m no scientist, but didn’t Wakefield fake data (modifying children’s histories, suggesting abnormal bowel function where there was none, modifying dates of onset of autism to make it coincide with the application of the MMR vaccine, stating there was no prior history of abnormal bowel function prior to inoculation when there clearly was). In which case critiquing it would be pointless. Garbage In Garbage Out.

If you want to learn more about the wakefield paper and controvers I found one of the origenal articles.

http://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c5258

It’s very detailed and interesting

A colonoscopy is an extremely unpleasant procedure. To perform a unnecessary one on a small child for anything other than sound clinical reasons is pretty cold-blooded.

Very interesting. I will openly say, while I understand your explanations and would encourage anyone studying or being otherwise in touch with scientific papers to read this, it’s very unlikely, I myself will be able to find the time and focus to ever do this. I think those who are venturing into the lecture of scientific papers should be aware that this is the right approach. You are so very right to remind people that science reviews (even of ‘serious sources’)are also interpretations and can distort the actual findings (or interpretations of findings by the scientists). I don’t think I am particularly dumb, but I know my limits, and it stuns me to see how many laymen (incl journalists or bloggers) have the pretense to be able to read and interpret scientific papers and how many others – unquestioning – accept their reading of something so complex and technique as truth. of course, this only came to my attention via the never-ending vaccine/autism “debate” following the agenda driven quax research that people still can’t let go. You view and dissection of what happened would be interesting, but I actually wonder if there are studies in completely different fields that have led to similar, unstoppable misinterpretation and hype, although there might have been multiple, more recent, more serious studies that have proven otherwise.

(this is a great blog discovery for me btw, not something I read over my cereals, but keep it up!)

I would quibble a bit about your statement that a reputable journal will be indexed in PubMed. I would expect that’s true in the context of this blog, but it is a rather specialized publication. Otherwise, thanks for this.

Concur – PubMed only covers medically-related material. Fields like Ecology, Engineering, much of the humanities will often be omitted – even some relevant chemistry journals (incl. one of my own articles). Scopus and Web of Knowledge are often broader but both are subscription-based. Conversely, if it IS in PubMed it’s likely reputable.

Edited. Thanks for catching that! I was in a biomed mindset when I wrote this, but it was pretty sloppy of me.

Another little trick is to find the paper on Google Scholar or something similar, and look for the little “Cited by X” link. On Google Scholar at least, clicking that link will instantly take you to a list of all the other papers that cite the paper in question. Kinda of like a reverse lit cited section.

Slight correction: all the other papers [books and presentations and things that Google Scholar finds] *that Google Scholar has the citation information for that cite that paper* – it is not complete, but it can give you some information about who is citing it and how.

Quite true, but if you then read those more recent papers, they will often mention papers that weren’t cited by the original paper, but probably should have been (maybe because they weren’t indexed by Google Scholar, and the author had no idea they existed), then you might do another forward jump, get another relevant paper, etc. until you have a complete picture.

This sort of procedure is a little beyond the scope of what was originally discussed, but more for someone in the field (or a student) who is writing a proposal or paper themselves. All tools and tricks have their weaknesses, the real trick is to use as many other tricks as you know to cover as many avenues as you can. Once you start getting less and less new information and start going in citation circles 99.9% of the time, you can probably say you have a good picture of the questions at hand.

I agree that for many scientific disciplines, reputable journals are not listed in PubMed. While that is a wonderful place to look for some disciplines, it is close to useless for others.

That’s true. Most of the archaeology journals I read, for example, aren’t on there. I should have posted a more thorough section on this. Apologies.

Terrific guide! I would just add one more thing about abstracts: Never trust the numbers in the abstract, because they often differ from the numbers in the body of the article. I believe that abstracts are often written well in advance of the rest of the article, possibly even before all the experiments are completed. Then when the authors add more data they forget to update the abstract. Another possibility is that the actual article is proofread more carefully than the abstract.

Thank you! That’s a great point. I wonder how many groups simply adapt the abstract from meetings presentations for the article. It might explain why data are sometimes missing. In any case, reading the abstract first (or JUST the abstract) isn’t the best practice, IMHO.

Sorry, but I really disagree with the post. Most science articles assume a huge amount of knowledge regarding the topic and nonscientists simply cannot substitute critical thinking skills (regardless of how excellent) and a brief “How to” post from you (again, regardless of how excellent) for real knowledge of the topic. Using all the points from you post I bet I could find an anti-vaccine paper or intelligent design paper or some such that passed all the tests. The material universe is not intuitive and making decisions regarding what is true and false about the material universe is not possible without a large amount of formal education.

Sorry! The post really does contain a lot of good stuff!

Probally true but those would be the exception not the rule. Also they are more likely to be legitment papers that an ID proponent has misread or mislabled. Like the ENCODE project.

Still this would remove about 98% of the bad material allowing people to at least try to make intelligent arguments (not necissarily correct arguments)

I agree that this is useful not just for laypeople, but for scientists-in-training! It’s a pretty involved process that you outline here, but good if you really want to judge the quality of the research rather than taking it at face-value.

One awesome approach I learned in a science communication course was to begin reading a paper not with the intro, but with the conclusion. It takes you right to the point: what are the authors claiming they have done? Then you go back to the intro to see how they motivate the problem and the background. I think after that came figures, and I forget the rest of the order (I usually do figures and enough of the methods to understand what’s going on, then read the whole paper top to bottom). Like you, I generally go to the abstract last – other than the initial abstract+title skim I did to decide to read the paper in the first place!

I was skeptical of this order at first, but for me it made a big difference in how quickly I could grasp what was going on in the paper.

Excellent list, I was looking for something like this to hand to my students. Would you mind if I provided it in the form of a handout for my students (with some minor modifications) with attribution? Any response is appreciated!

Of course, feel free!

You left out discolsures/funding/competing interests.

You’re right! Darn it. Thanks for catching that.

You have something in parentheses:

“Scientific words have extremely precise meanings”

…which I think should be bold, possibly italicized, maybe flashing, and perhaps made into a reverse tattoo on the foreheads of some people.

I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve gotten into ridiculous arguments about easily proved information, only to discover that the other person had no idea what I was saying because there were a few key words that they’d misinterpreted. Often these were words that they had previously guessed the meaning of, given the context, rather than take the time to look the words up. They were close enough that we both thought we were talking about the same thing,

Reblogged this on Bloggin' Bray and commented:

This looks like a great potential assignment for undergrads learning to read primary literature. Senior sem students: this is a little bit of overkill for you guys at this point, but it’s worth reviewing and using for denser/difficult articles.

Reblogged this on Things that only exist in my head….

Excellent post. It is interesting that your suggestion for reading the methods is how I design experiments! The order i write a paper is: Title, Tables/figures, Results, Methods, discussion, Introduction, Abstract.

My only suggestion is to keep the methods “diagram” in front of you when you look at the data.

An example of misunderstanding science: I’ve seen a claim that, since hydroxyl ions have oxygen in them, alkalis must be a good way of oxygenating your cells.

Hi Jennifer,

Very nice posts–Steve is very proud (he put me on to this) and rightly so! I’ll add my two cents on paper reading, since I’ve read a few (but not as thoroughly as you suggest). The first thing I look at is the final paragraph in the introduction. That’s where the authors most succinctly say what they intend to show in the paper, without actually providing data or making conclusions.

On the previous post, let me also offer a thought that came to mind after reading it. I believe that one of the reasons it is becoming difficult to make the case for vaccination is that there is no proof to the individual that it worked. It might hurt, and there is a low risk of unfortunate side effects. And someone is making a profit from doing it, although it is truly small compared to most other medical interventions. If you look around you, though, the number of people you see or know with devastating illnesses is very low. We aren’t desperate to be protected from polio any more, because it isn’t a real disease to us. And chicken pox isn’t really that bad, is it? It’s easy to find the whole process to be a hoax and make yourself a caring, thoughtful her for protecting your children from exposure to vaccines.

I’m afraid none of this will do any good if we don’t first teach what a CREDIBLE source is. There are so many papers that read (to the layman) like scientific papers that I often get bombarded with dissenting claims that my friends think are totally credible. I’ve started asking the questions:

1- Is it peer reviewed?

2- Is it sponsored or published by an organization that profits form a specific result?

3- Is it supported by other peer reviewed studies.

If I get one more “proof” of the Great Flood from Answers in Genesis or “research” by “natural healing herb” sites…

Thanks just what I need to help me do a critique

This is really thorough and very well done. Thank you for this I will be sharing it widely!

This is a useful tool when reading research papers with lots of jargon:

http://reflect.ws/

You can paste the url of a paper, and the website will mine the text of the article for known terms and present an annotated version with links to wikipedia and numerous databases. They also provide plugins and an API.

Although there is much to disregard with postmodernism, one thing that I believe that will be very useful in its engagement – especially to the scientific community – is the acknowledgment that everyone has biases and that they who control the “legitimization” of data and interpretations are amassing power to themselves. If scientists think they are “unbiased” and that “contrary theories” are welcome need only peruse certain topics and discussions to realize that it is an illusion of their own minds. And “peer review” is merely another way of saying that one must be accepted in the club before one’s research gets acknowledgment. Only when the proof becomes so obvious that it cannot be denied are contrarians accepted. I have found the scientific community to be among the most narrow minded – and mean spirited – groups in society.

I concur E.! I did a paper on publication bias while in school and found exactly the same things you mentioned to be true. I believe the only way to circumvent this is to have all trials registered before they begin and transparency about results. Whether negative or positive results this is the only way to get as close as possible to factual information

Comments like this are often ignored because they make sense. Scientists are people too whether they want to admit it or not – and are full of biases, prejudices, fear, and reject evidence that doesn’t fit their naturalistic worldview before even considering it. And boy, can they get nasty!

Thank you for taking the time to put this together. I do think that students and researchers evolve greatly in how they read papers. Students often get lost in the details, vocabulary or limitations of the study and this is a nice framework. I just wanted to add two points.

1) Is the study driven by an interest in quantifying a pattern or by addressing a hypothesis (cause and effect)? In my lab, when we read scientific a papers, I ask the students to not only pull out the question (is there one?) but also to ask themselves whether a hypothesis was actually tested. We begin by reading Guy McPherson’s 2001 paper “Teaching & Learning the Scientific Method”.

Click to access Teaching&LearningSciMethod_McPherson.pdf

I find that a lot of papers just quantify a pattern and call it a hypothesis or don’t even have a hypothesis. A paper does not need to test a hypothesis to be effective and important, it is just important that a student understand the difference as they are constantly told that studies test hypothesis. Thus lay people constantly think that the study tested whether a cause and effect mechnism was involved. You’d be surprise how badly we mangle this in papers. For example, most of the science news that you hear on NPR in the morning has to do with patterns “researcher found that people taking a given drug are more likely to …” or “research have found a link between X and Y” but the researchers have to do follow-up studies to test possible mechanisms (hypotheses) behind the results. I have taught graduate level field courses and sat in on a lot of committees and realize that students and researchers often don’t know the difference.

After reading the paper we discuss whether the results support the proposed hypothesis and conclusions. If there is no hypothesis, we discuss how the paper could have been framed or study could have been conducted to test a hypothesis. Sometimes we just discuss how these results can then help us develop hypotheses.

The best hypothesis testers are Click and Clack the tap-it brothers on car talk. They have a question they need to address, they make observations and come up with hypotheses and predictions that woudl support their hypotheses.

2) I am not sure if it is just a style issue as I don’t completely understand how you might approach this exercise with students, but I don’t think it is correct to emphasize that scientists test null hypotheses (that there is no difference). I personally think we emphasize the null hypothesis so much that we neglect what the focus of the paper is. The null hypothesis is important and understanding what the null you are testing against is important, but it is a statistical issue. A student should focus on the alternative hypotheses and predictions that would support such hypotheses. Then, the students can envision how you would test each prediction and what statistics will be used to determine whether a pattern exists (this is when the null hypothesis is important).

Thanks for your posts!

Reblogged this on An Indifferent Port and commented:

Very informative piece which aims to give laypeople the confidence and the tools to tackle scientific literature.

This is fantastic. Your note on significant vs non-significant makes me wish for a follow up article on confusion from other jargony uses of common words. (For example, “characterize” carries a far more concrete connotation in science than in lay English.)

This is an interesting post, and it’s a detailed and undoubtedly useful guide to how to read the right scientific paper. My worry – as someone who works in a technical field with lots of non-specialist volunteers (see http://www.zooniverse.org) – is that it will, taken literally, result in a lot of time spent on the wrong papers.

When I set out to read a paper, I’ve usually found it via a literature search. I’ve picked it over thousands of others that I might read and tens of others I probably should. My first goal is to establish whether it’s worth the time spent in actually understanding every step, and to do that it’s not necessary to take the time to work through methodically in the way you describe – in fact, to do so would be destructive as it takes a lot of time to do properly. Instead, I’d recommend skimming the introduction and the conclusions ignoring words you don’t understand to see if there’s anything there that makes you stop and go ‘I wonder where that came from’. Then I’d look at the figures (usually easier to understand than the words) to see what the rough outline of an argument is. Only then would I decide to go and work through the rest of the paper.

My worry is that without learning to skim, then most people encountering most of the literature will miss out on an essential scientific skill – the ability to decide what’s relevant. You can’t get that by close reading a single paper.

Good point Kevin. Even grad students will read a great deal and not really understand why it is relevant or how the paper fits into the grand scheme of the question/ subject they want to better understand. This seems ability to find important relevant sources and assess them briefly are skills that are developed over time. However, understanding this issue, this blog focuses, on “given a paper, how should one approach it”?

This is a great guide for something a lot of people struggle with, well done. One thing I’d kind of quibble with though is your reference to review articles. They aren’t all the same thing, at least in the healthcare literature. Systematic reviews (such as those published on the Cochrane Database) are a very different creature to your common literature review and can be a stronger source of evidence than single studies as the authors have included all the relevant studies on the subject and may have been able to give a pooled (meta-analysed) finding of effect. Handily for lay people, Cochrane reviews also include a plain language summary of the methods and findings. I’m seeing systematic reviews cited more and more in arguments about various science issues, so it’s probably worth including them in any discussion of interpreting scientific literature.

Reblogged this on Online and commented:

Great article!

Do you have any suggestions for digesting a paper that is less time consuming? I rarely have this much available time, but still want to understand.

Only when the scientists and marketing experts who actually write these papers, and the publications that publish them, do what sports people do and clearly display the logos of their sponsors on their documents, will it be possible to make a truly informed decision about how reliable these papers are. When a pharmaceutical company has a vested interest in proving that a drug or vaccine they produce is safe, they have many methods to ensure that the test parameters exclude those who are adversely affected by this drug or vaccine, and simply move these cases to the ‘dropouts’ so they don’t have to include them in the results; thereby ‘proving’ exactly what they set out to prove. Read Dr David Healy’s ‘Pharmageddon’ for the inside story.

Thank you so much for this article! I’m in the midst of numerous arguments with people who love to quote/cite absolutely crap lit, simply because they have no idea how to read it and understand WHY it’s crap. Frustrating, to say the least. I’m getting ready to write a blog article along these lines myself, and have Evernoted your article for citations. I promise to reference you and link back properly.

A great post, and your suggestion is absolutely a recommendable way of reading articles.

I sometimes take another approach. In areas I am familiar with, I like to skim through the abstract to get an idea if the article is relevant at all (The title is usually what catches my attention). But then I go to the materials and methods section. This is where I form an opinion if the article at hand is worthwhile studying closer.

You are right that the abstracts aren’t always helpful in understanding the findings – sometimes there is even discrepancy between the abstract and the text. I wholeheartedly agree with your strong warning against using the abstract in a discussion unless you have read and understood the full article.

It’s pretty hard for non-academic, non-scientific folks (“laypeople”) to access many of these articles — they’re usually $10-20 a pop unless you’re affiliated with an institution that has access. No?

Unfortunately, that’s sometimes true. Journals are supposed to make the articles freely available after 6 months (doesn’t always happen) You may also be able to get them free or cheaply through inter-library loan.

@ Greenie

That’s true. And sometimes they are even more pricy. So it is understandable that many people just stick with the abstract.

But it is still a bad idea to use abstracts only. It is also noteworthy that many good quality articles are published by open-access journals. Also many systematic reviews are available for free, and they are good starting points. These are not the subject of this post, but they are certainly worthwhile looking for.

As an undergrad Psych student (at Dartmouth,), much of our core course requirements consisted of review of important experiments in the discipline. The lab “write-ups” were in the style required for published articles. An entire course in Statistics, taught by a Prof whose original PhD was in Math, was required concurrently with core courses for the major. We were required to conduct and eventually design experiments in a manner that would be both valid and publishable, as if they were original and had not been a repeat of “the Greats”. As a senior, some of our work was in fact on not-previously published grounds.

These skills in applied skepticism were very helpful in my business career.

I see the most ignorance, and in many cases willful ignorance, in current writings about “Climate Change”. Many ‘review” articles are written purporting to show the “consensus”, and often the deck is stacked in the way articles are selected to be included in the so-called “review”. Drilling down into the primary articles, most show absurdly small differences in modest data sets with large variations. Selection of data is usually weak and often arbitrary (“Well, it’s all we have from that era,” seems to be a common reason for reporting some modest analysis.) Probabilities of statistical results are generally unreported, and certainly are nothing like p = .1 or .05. Yet these sketchy results are taken as gospel by the gullible, collected and reported as “consensus” in biased sample “review” articles, and then trumpeted loudly in agenda-driven media.

Of course, there’s a lot of money at stake inside academia, and even more outside.

Sheesh!

You have stated that this guideline is aimed at making the non-scientist able to deal with research papers, and to make intelligent judgements.. I think it is very rare that many will bother.. The very nature of the peer reviewed article, as well as it’s stylistic demands seem to be designed to set the scientist in a world of his/her own.

I really wish that there were more “clarifiers” of scientific literature. So much of science is concerned with issues that effect everyone. (should I vaccinate my baby, what can we do about climate change, how can I make sure I am feeding my family healthy food, etc.)

It is unfortunate that there are so few who have credible scientific credentials who are willing to write for the general public. It is unfortunate because people don’t appreciate when someone learns something amazing, and only a few peers “get it” It is also unfortunate from a public policy viewpoint where people are being led to accept bad science, or bad scientists as the rational for public policy.

Super informative step-by-step instructions for the non-scientist. I am one of those non-scientist bloggers fascinated by scientific topics. Through trial and error, I have been forced to dig deeper and not blindly accept what is said on the first click away from my google search. It is far easier and less time consuming to believe psuedo-science than it is to roll up your sleeves and dive into research papers. I am reblogging this at sleuth4health.wordpress.com

Reblogged this on SLEUTH 4 HEALTH and commented:

In my continuing quest to understand scientific topics such as GMOs, I find articles like this a huge help. There is just no easy way to get the facts. One must roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty with science, i.e., jargon, tables, methods, abstracts and conclusions.