There’s been a lot of discussion in the news over the past few days regarding the recent report that four out of ten households with children in the United States are now headed by a “female breadwinner.”

This has cultural and economic implications that make for a lively political debate. And while I’m enjoying it in all its glory, there’s one particular aspect I want to respond to here. Specifically, these comments by pundit Erick Erickson:

I’m so used to liberals telling conservatives that they’re anti-science. But liberals who defend this and say it is not a bad thing are very anti-science. When you look at biology, when you look at the natural world, the roles of a male and a female in society and in other animals, the male typically is the dominant role. The female, it’s not antithesis, or it’s not competing, it’s a complimentary role.

He then doubled down on his position in a subsequent blog post responding to the critical backlash he received:

I also noted that the left, which tells us all the time we’re just another animal in the animal kingdom, is rather anti-science when it comes to this. In many, many animal species, the male and female of the species play complementary roles, with the male dominant in strength and protection and the female dominant in nurture. It’s the female who tames the male beast. One notable exception is the lion, where the male lion looks flashy but behaves mostly like a lazy beta-male MSNBC producer

By invoking science to justify his ideology, Mr. Erickson opens all his statements up to factual scrutiny.

There have been some really wonderful critiques of Mr. Erickson’s position, including this one by Amanda Marcotte, and Megyn Kelly’s interview here:

(One particularly memorable quote: “And who died and made you scientist-in-chief?” )

Indeed. Also inconveniently for Mr. Erickson’s position, not all animals structure their family roles in the same way as a traditional American household from the 1950s. [References for the information I present here are listed at the bottom of the page.]

What he’s clumsily referring to is something known as parental investment, and it’s a phenomenon which has been very extensively studied by ecologists and evolutionary biologists. Parental investment refers to the amount and kind of energy an organism devotes to its offspring in order to improve their survival chances. Parental investment takes many different forms, including pregnancy, territory defense, nest or bower building, grooming, protection, and food provision (or production, in the case of lactation). There are a great many potential trade-offs to this behavior, including energy expenditure, possible sacrifice of other mating opportunities, and potential exposure to predators in order to ensure offspring have better outcomes.

Among animal species, there exists both uni-parental care (one parent solely provides for the offspring) and bi-parental care (both parents contribute). The production of eggs tends to demand a greater expenditure of resources than the production of sperm, and usually in species with internal fertilization (the female carries the embryo to term), the female parent is heavily invested in each pregnancy and subsequent care of the offspring. It’s the extent to which the male is involved that is most variable. So already we see that Mr. Erickson’s partitioning of males and females in the natural world into “providers” and “nurturers” is incorrect: the female nearly always does the bulk of both “nurturing” and “providing” (and “protecting”, for that matter). There are some exceptions: Males do provision the offspring exclusively in a number of organisms, including many types of fish and bugs, but not in mammalian species. Bi-parental care can be found in a number of other organisms (including coyotes, marmosets, some bugs, and some birds).

But what about our closest relatives, primates? Surely if we were to draw lessons from the natural world about how to structure human families in a “natural” way, it would be from them!

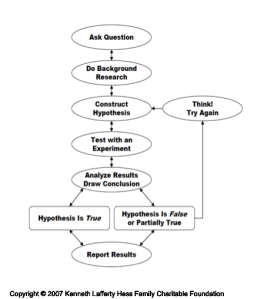

This table compares the behavior of different primate species with their mating strategies (monogamy, single males with multiple females, and multi-male, multi-female groups). Here male care is broadly defined to include behaviors such as carrying, provisioning, grooming, and protection

As you can see, there are quite a variety of ways in which primate families are structured. This is also true for humans, where cultural practices and personal choice play a significant role alongside environmental demands and biology in influencing marriage patterns and the ways in which males and females care for children.

So, Mr. Erickson, when it comes to the natural world, one can’t find easy justification for your essentialism. You cannot just claim the mantle of scientific authority without earning it honestly through a minimum of research to make sure your assertions are factual. Do better next time, or you’ll simply embarrass yourself further.

———————————————————————————————————–

References:

Gross. MR. 2005. The evolution of parental care. The Quarterly Review of Biology 80(1): 37-46 (http://academic.reed.edu/biology/courses/BIO342/2012_syllabus/2012_readings/Gross_2005.pdf)

Geary, D. C. (2005). Evolution of paternal investment. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The evolutionary psychology handbook (pp. 483-505). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons

Smiseth PT., Kölliker M, and Royle NJ. 2012. What is parental care? In The Evolution of Parental Care, First Edition. Oxford Univerity press

Zeh and Smith 1985. Paternal Investment by Terrestrial Arthropods. Integrative and Comparative Biology 25 (3): 785-805 (http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/content/25/3/785.short)