I haven’t been writing as much here recently, because I’ve been working on a “News and Views” article for Nature….and now I can finally talk about it! Here’s a link to my article: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v506/n7487/full/506162a.html, and to the paper that it’s discussing: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v506/n7487/full/nature13025.html. In the next few days I’ll post something here to discuss the main points of the article (for those of you who can’t access it), and also my reaction to the media coverage that the study is getting.

Science

How to tell if an ancient DNA study is legitimate

It seems that every week there are exciting new findings from ancient DNA research. This is wonderful news, because we’re learning incredible things about the relationship between humans and Neandertals, the prehistory of ancient populations, and even previously unknown hominins. But on the flip side, we’re also seeing news reports of extremely questionable results, and I’ve gotten more than one inquiry recently from people excited or confused by them. I though it would be a good idea to write a bit about how regular people can figure out whether a study is legitimate or not.

The first step in distinguishing good ancient DNA studies from bad ones is the same as distinguishing pseudoscience from legitimate science in general: ask where the results are published. Are they in a peer-reviewed journal? Or does the author present it as “science by press release,” stating something like:

The next steps require you to know a bit about ancient DNA itself, and how research is conducted. What most casual readers may not understand is how difficult recovering DNA from ancient remains is….and how easily it can become contaminated.

The TL;DR version is that for an ancient DNA study to be considered authentic, at minimum it:

- Must be conducted in the proper facilities

- Must be conducted by personnel practicing sterile techniques

- Must utilize negative controls

- Must have a subset of results reproduced by an outside laboratory

- Must yield phylogenetically reasonable results (or produce extraordinary evidence to support unusual results), that match the characteristics of ancient DNA.

- Must conform to any additional standards necessary, depending on the sample and experimental design

Here’s why:

“Scientists should tithe ten percent of their time on public education…” –Carl Sagan

We were wrong about Bill Nye

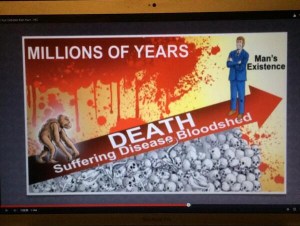

Many of us in the scientific community have a longstanding policy not to debate with creationists, in part because doing so gives an unwarranted credibility to their disingenuous arguments. So when Bill Nye chose to debate Ken Ham in the Creation Museum on whether creationism was a viable explanation for life, there was a lot of wincing and predictions that Nye would unintentionally do damage to public perception of evolution. I was also skeptical that this debate would do any good. But I think that most of us scientists had overlooked the fact that Nye is an experienced entertainer as well as science educator–a combination of traits that most of us don’t possess, and one perfect for this venue. Nye did an astounding job at calmly explaining the overwhelming evidence for why creationism (with special attention to Noah’s ark and the flood) simply couldn’t explain the origins and diversity of life on earth. Ham, on the other hand, seemed really flustered and didn’t even make an attempt (beyond trotting out token creation scientists in an attempt to give creationism some legitimacy) to address the questions at hand with evidence. He was completely out of his league, and it showed.

One of the most telling parts of the debate was the question that was asked of both men: “What, if anything, would convince you to change your mind?”

Ham’s answer: “Nothing.”

Nye’s answer: “Evidence.”

I really encourage you to watch the entire debate here, but if you’re not up for three hours of viewing (and I don’t blame you), you can see shorter excerpts and an interview with Nye here.

And here are some other reactions to the debate:

http://wonkette.com/541213/bill-nye-expert-at-explaining-science-to-children-finds-it-too-complicated-for-a-creationist

http://scienceblogs.com/gregladen/2014/02/05/who-won-the-bill-nye-ken-ham-debate-bill-nye/

Nye was right to do this debate. Not only did he win with excellent presentation and overwhelming evidence, he managed to convey to viewers the beauty and humility of the scientific process. Nye didn’t have any problem saying to some questions: “I don’t know–but I can’t wait to find out!!!”: the motivation that drives every single scientist when he or she goes to work in the morning. If nothing else but this gets conveyed to the people who watched the debate, I’d still be pretty happy. I don’t know if the people in the Creation auditorium had ever heard the evidence he presented before. (They seem to be proud of their lack of understanding of evolution). I doubt he changed any of their minds, but I can’t help but wonder if some of the people watching the stream went to bed last night with a slightly better understanding of the scientific process. I hope they did.

Guest post on peer review on the PeerJ blog –>

How to be a good graduate student

Continuing the “How to be a good scientist” series of posts that I have been doing here lately, I wanted to call your attention to this excellent piece written by Indira Raman (of my former institution, Northwestern University): “How to Be a Graduate Advisee”. I recommend all scientists read it, regardless of what stage they’re at in their career, because much of its advice applies to doing science in general.

Here are my reactions to a few points that I particularly appreciated:

“The science you are doing is the real thing. Although many students do not immediately realize it, graduate study is not a lab course, not a summer experience, not an exercise for personal enrichment.You are a real, practicing scientist, albeit a trainee, from day one”.

It is important for a young scientist to feel part of a larger community. At my graduate institution, a small but meaningful way that the program emphasized this was to explicitly request that members of the department at all ranks address each other by first names only. On day 1 of our graduate orientation, we were told “You are our colleagues now, so don’t use titles with us.” Small things like that make a very big difference to young graduate students. As a graduate student, take pride in your work and understand its context with respect to the rest of your discipline.

“Do not let yourself get accustomed to failure…..every day you should be able to account for what you did: practice articulating for yourself what worked, and what you will do differently tomorrow. The worst thing that can happen to you scientifically is to get used to going into the lab, doing a procedure in a fixed way, getting no useful result, and going home, with the sense that that is all that science is. You must see movement on your research, not necessarily as daily data, but as a sense that what you did today gets you closer to an outcome”.

I think this is the best piece of advice a graduate student could read. Mistaking motion for action is an easy trap to fall into, and I’m constantly struggling with this. I don’t have any great insights into how to “cure” this problem, besides offering what I do: when I recognize that I’m in a rut, I step back, reevaluate, talk to my PI or colleagues, and try a new approach. Sometimes even something as simple as taking a day off to go hiking and just brainstorm is enough to get myself back on the right track. While I’m in this mode, I try to ask myself at the end of the day what I specifically did to move myself closer to a larger goal. What do I need to do differently tomorrow? A tool that I often use for breaking things down into the critical “taking action” tasks vs. the optional ones is the “Today and Not Today” smartphone app. Don’t get hung up on the specifics, though–just find something (a tool, a protocol, a confidant) that works for you and use it!

“Cultivate the ability to get inspired. When you see other people excel scientifically—your peers or seniors—you can have several reactions. One is to dismiss those people as extraordinary, perhaps contrasting them with yourself so that you feel dejected or inadequate. A second response is to put those people down by criticizing an unappealing attribute that they have. A third, and perhaps the most constructive, reaction is to look at those people’s abilities as something to aspire to. What can you learn from them?”

Several years ago when I lived in Utah, I was invited to train at Gym Jones. Being surrounded by athletes of the highest caliber fundamentally changed my outlook–not only physically, but also professionally. It might seem odd that a gym could help me become a better scientist, but physical training was only a means to an end. Exactly what I learned there is a subject that could fill an entire post. But reading the point above reminded me of one particular core philosophy of the gym, articulated here by Mark Twight:

“You become what you do. How and what you become depends on environmental influence so you become who you hang around. Raise the standard your peers must meet and you’ll raise your expectations of yourself. If your environment is not making you better, change it.”

To become a better graduate student, you need to surround yourself with scientists who are better than you, and whose work inspires you to become better yourself. If you can’t find them in your own department, at the very least you should be following the work of the leaders in your field. Twitter is a good place for this, as are blogs and books. For example, here is a book that inspired me last year.

At the same time, recognize the dangers of imposter syndrome and know what is reasonably expected of you at each level. Comparing a graduate student’s scientific accomplishments to those of a tenured professor is inappropriate. Try to learn something from every experience, and from every person you encounter.

Raman goes on to talk about a number of other excellent points, from how to work with one’s advisor, to how to maintain one’s scientific ideals. I strongly recommend you take a look!

Thanks to @mwilsonsayres (http://mathbionerd.blogspot.com/) for the link!

The placid progress of science

Today’s hike resulted in a metaphor.

Is evolution in trouble?

According to a recent article in the Daily Beast by Dr. Karl Giberson, 2013 was a terrible year for evolution for several reasons:

“The year ended with the anti-evolution book Darwin’s Doubt as Amazon’s top seller in the “Paleontology” category. The state of Texas spent much of the year trying to keep the country’s most respected high school biology text out of its public schools. And leading anti-evolutionist and Creation Museum curator Ken Ham made his annual announcement that the “final nail” had been pounded into the coffin of poor Darwin’s beleaguered theory of evolution.

Americans entered 2013 more opposed to evolution than they have been for years, with an amazing 46 percent embracing the notion that “God created humans pretty much in their present form at one time in the last 10,000 years or so.” This number was up a full 6 percent from the prior poll taken in 2010. According to a December 2013 Pew poll, among white evangelical Protestants, a demographic that includes many Republican members of Congress and governors, almost 64 percent reject the idea that humans have evolved.”

The Most Important Playground Conversation: How to Persuade a Friend to Vaccinate

by Colin McRoberts

A while back a friend asked me to help with a difficult conversation. Someone she cared about was expecting her first child, and had decided not to vaccinate her baby. My friend desperately wanted to change the mother’s mind to protect that child. But she wasn’t sure how to proceed. She had the facts on vaccines, and knew that refusing immunizations was a dangerous and irresponsible decision. But she wasn’t sure how to convince her friend of that without jeopardizing their relationship. There are some excellent resources for health care providers having this conversation with patients. But there wasn’t much that applied to her particular situation. So she asked me whether my experience as a negotiator gave me any insights that might help her plan for what was sure to be a difficult conversation.

As it happens, I had been thinking about the same thing. I’m particularly interested in how laypeople should approach a conversation like this, since laypeople can be much more persuasive than the family physician. In the real world, our family and trusted friends very often carry more weight than experts. The giant but useless homeopathy industry would collapse otherwise. So when you hear that one of your friends or relatives doesn’t plan to vaccinate, you have the opportunity for a conversation that could potentially change their mind and save that child from terrible harm.

Unfortunately, too many people approach that conversation timidly, without a solid strategy for persuading their friend. That makes it hard to respond when things take an unexpected twist, such as your friend spouting off antivaxer talking points you hadn’t considered. Other people are too aggressive, treating the conversation like the comments section of a blog post. That kind of combative and confrontational dialog can feel good, but it doesn’t accomplish much in the real world.

So what does a strategy for an effective, persuasive conversation look like? There is a world of advice we could give about that conversation. We’ve distilled it into four basic points: be sincere, ask questions, be sympathetic, and provide information.

After the fold, we’ll go into some specific thoughts about each one. We want to stress, though, that this is just a framework. The conversation itself will be different every time. We want to know more about your conversations. If you’ve tried to talk someone into getting a child (or themself) immunized, please share your story in the comments section.

Continue reading

How to become good at peer review: A guide for young scientists

Peer review is at the heart of the scientific method. Its philosophy is based on the idea that one’s research must survive the scrutiny of experts before it is presented to the larger scientific community as worthy of serious consideration. Reviewers (also known as referees) are experts in a particular topic or field. They have the requisite experience and knowledge to evaluate whether a study’s methods are appropriate, results are accurate, and the authors’ interpretations of the results are reasonable. Referees are expected to alert the journal editor to any problems they identify, and make recommendations as to whether a paper should be accepted, returned to the authors for revisions, or rejected. Referees are not expected to replicate results or (necessarily) to be able to identify deliberate fraud. While it’s by no means a perfect system (see, for example, the rising rates of paper retractions), it is still the best system of scientific quality control that we have. In fact, it’s such a central part of the scientific process that one can often identify questionable scientific findings by their authors’ objections to the rigor of review (and attempts to circumvent it by a variety of methods, including self-publication).

Yet the quality of this system is ultimately dependent on the quality of the reviewers themselves. Many graduate programs don’t explicitly teach courses on how to review papers. Instead, a young scientist may learn how to review a paper under the guidance of his or her mentor, through journal clubs, or simply through trial and error. I’ve been thinking about this topic a lot, and decided to put together a set of guidelines for young scientists. In doing so, I also hope to help non-scientists understand a bit more about the process.

I intend for this to be an evolving post, so I ask for my colleagues’ help in improving it. At the end the post, I’m assembling a list of resources for further reading. If you have any suggestions or resources, please send them to me and I’ll add them. Continue reading